By Bishop Sophie Relf-Christopher

Sorry, we got it wrong

In our rush to make Christianity more palatable for each new cultural mood, we’ve often misdiagnosed the real challenge and misread the moment. We quietly decided that practices like fasting, living with mystery, or going on pilgrimage were too old‑fashioned to bother reviving. I’m convinced we were wrong.

Secular culture is now busy reinventing some of these demanding spiritual habits – digital detoxes, wellness retreats, mindfulness bootcamps – while carefully leaving God out of the picture. So maybe this is the time to dust off the treasures of our own tradition and ask, with some holy curiosity: what if the way forward is hidden in the “old” practices we’ve neglected?

Rediscovering Lent’s power in an age of luxury and indulgence

Most of us live with a level of safety and excess that first‑century Jews and Gentiles couldn’t have imagined. We outstrip ancient royalty in lifespan, comfort, and constant access to food, medicine, clean water, factory-farmed meat, and everyday luxuries. That’s exactly why fasting has never been more out of step with ordinary human life – and never more needed. Our shifting appetite for fasting isn’t just about willpower; it’s a story with historical, theological, missional, and deeply practical threads.

Biblical foundations of fasting

Christians don’t fast in a vacuum. We stand alongside Jews and Muslims in remembrance of the fasts of Elijah, Esther, and many others in the Old Testament. At the centre of our tradition is Moses’ 40‑day fast on Sinai, during which he remained with God to receive the Ten Commandments (Exodus 34:28). This pattern is echoed in Jesus’ 40-day testing in the wilderness (Matthew 4:1–11). For both Moses and Jesus, their fasting is a radical act of dependence, trusting God’s grace rather than their own bodily reserves.

For Christians, one of the most compelling reasons to fast comes straight from Jesus’ mouth. In Matthew 6:16 (NRSV), he says, “whenever you fast, do not look dismal, like the hypocrites, for they disfigure their faces so as to show others that they are fasting.” He doesn’t say if you fast, as though it were an optional extra, but whenever you fast – because he assumes his disciples will do it. The real issue is not whether we fast, but why: fasting is meant to draw us closer to God, not draw attention to ourselves.

Fasting – a quick zip through time

From the very beginning, Christians have fasted. In Acts 13:2–3, the church fasts as it listens for the Spirit’s call to send Barnabas and Saul, and by the first century, regular communal fasts on Wednesdays and Fridays were already part of Christian life. In the third to fifth centuries, the Desert Mothers and Fathers took this further, using fasting to cultivate humility, and in 325, the Council of Nicaea drew together diverse practices into the now-familiar forty days of Lenten preparation for Easter (excluding Sundays).

Over the centuries, monastic communities embraced regular fasting and abstaining from rich foods, even as the Reformers debated its value – Luther wary of empty ritual, Calvin reframing fasting as spiritual warfare against self‑indulgence. Fastforward to secular Australia in 2026, where church numbers and public Christian voice have both waned and many of us have quietly sidelined fasting as too off‑putting. Perversely, this may be just when disciplines like this might most clearly mark out a distinctive, resilient faith.

The vapid secularisation of fasting

At the same time, intermittent fasting, caffeine detoxes, juice cleanses, and carb fasting are commonplace in 2026. One of the strangest things about the situation is that secular society seems less embarrassed to fast than Christians, and the fasts people choose are sometimes quite loopy: phone zombie fast – no walking while reading your phone, selfie fast – trying to resist the urge to touch up photos of yourself for the internet, food delivery fast – pretty much as it sounds, and Netflix episode fast – where you wait a long time between episodes of your favourite show (perhaps 40 days?). Most of these are nostalgic of a bygone era but contain little that might uplift the soul.

Is Christian fasting too retro to revive?

Self-discipline that focuses our hearts on God is not wasted – indeed, God bids us gather up the crumbs of every situation because nothing is wasted in God’s economy. Self-discipline offered in solidarity with the poor of the world is not wasted. It keeps us zealous for justice for those who are downtrodden. Self-discipline in preparation for Easter makes the feast and celebration meaningful. It is the extension of the impulse by which many of us wait for Good Friday to eat hot cross buns or wait until Easter Sunday for chocolate eggs. The truth is, it is not a feast if you haven’t fasted.

Fasting ideas in the age of pleasure

Puritans in every era probably thought their own era was the most hedonistic. However, when we look at the appalling ways human beings, animals and God’s world are exploited for the rich today – both online and in person, in an age when we should know better – the 2020s could give any century a run for its debauched money. We are very good at chasing instant gratification and far less interested in getting right with God. Any act of self‑discipline offered to God in a shortsighted culture is a quietly radical witness.

Yet our world is very different from the first century, so our fasts need to fit real modern lives. Please do not go days without food or water: that is dangerous, and it does not carry the same meaning for people who are not living hand‑to‑mouth. Why not try something new this Lent?

Hedonistic consumption fasts

Adelaide has serious economic inequality. One Lenten discipline could be to resist consumerism: stop buying beyond what you truly need, so you do not slide into believing you “deserve” more – by your own effort – than other Australians living in financial hardship. Consumerism is a subtle, powerful trap.

Digital fasting

Does the idea of being off your phone, iPad, TV and computer sound almost heavenly? A total digital fast might help you step away from activities that drain your spirit and steal time from friends, family and neighbours.

Fasting from inattention

Fast from entitled inattention by keeping a daily gratitude diary. This simple practice has proven psychological benefits and trains you to see your life not as “the bare minimum”, but as overflowing with gifts from our loving God.

Modified eating

For many, fasting from food has been hijacked by diet culture. So many people are already restricting themselves that eating disorders are at record and rising levels. Rather than cutting out food, you might choose to go without excessive sugar, meat, alcohol, or some other richness that makes spiritual sense for you.

Fasting from a sedentary life

If your body allows it, choose to move more during Lent. A discipline that strengthens you physically and spiritually can enlarge your capacity to be present, energetic and available for God’s mission. I once preached this message, and a man in the congregation became very focused on his fitness and is still working hard in his parish to this day, bench-pressing 120kg!

If the Lenten train has left the station by the time you read this, do not despair. You can jump on board as you are today and find a disciplined fast that you offer to God, to make sense of the feast that lies ahead.

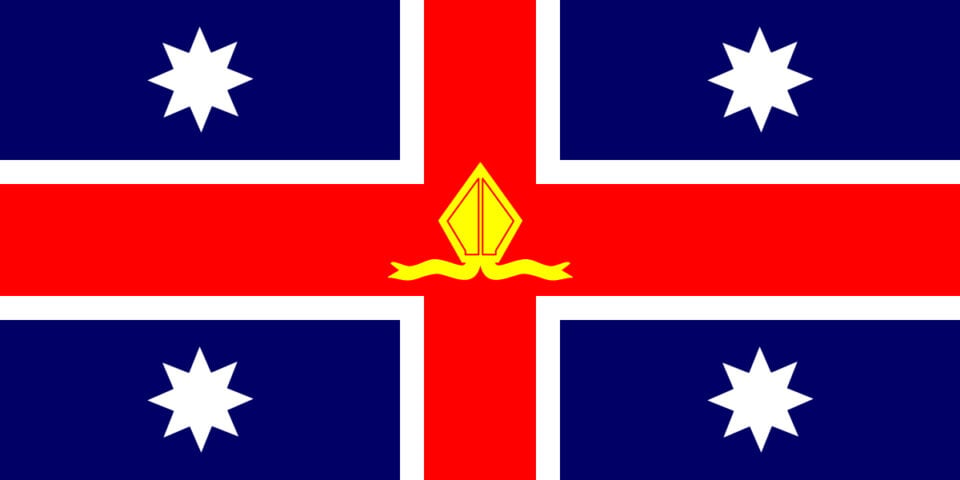

The Right Rev’d Sophie Relf-Christopher is Administrator (Sede Vacante) of the Diocese of Adelaide