By the Rev’d Assoc Prof Matthew Anstey, May 2025

The first trial in the Anglican Church of Australia of my new liturgical translation of the Psalms, now called The Anstey Psalter commences on Sunday 15 June 2025 and runs for seven weeks. So far about 40 Anglican churches and schools have registered for the trial and we expect more to join.

I have been working on this project for several years and it is anticipated it will take another five or so years to complete. You can read more about the project, and parishes/schools can register to participate, at www.ansteypsalter.com.

The psalm for each Sunday Holy Communion service is always chosen as a response to the first reading, typically an Old Testament reading. Together, all the readings follow a three-year cycle, called The Revised Common Lectionary and this cycle is followed by most (mainly non-conservative) churches around the world.

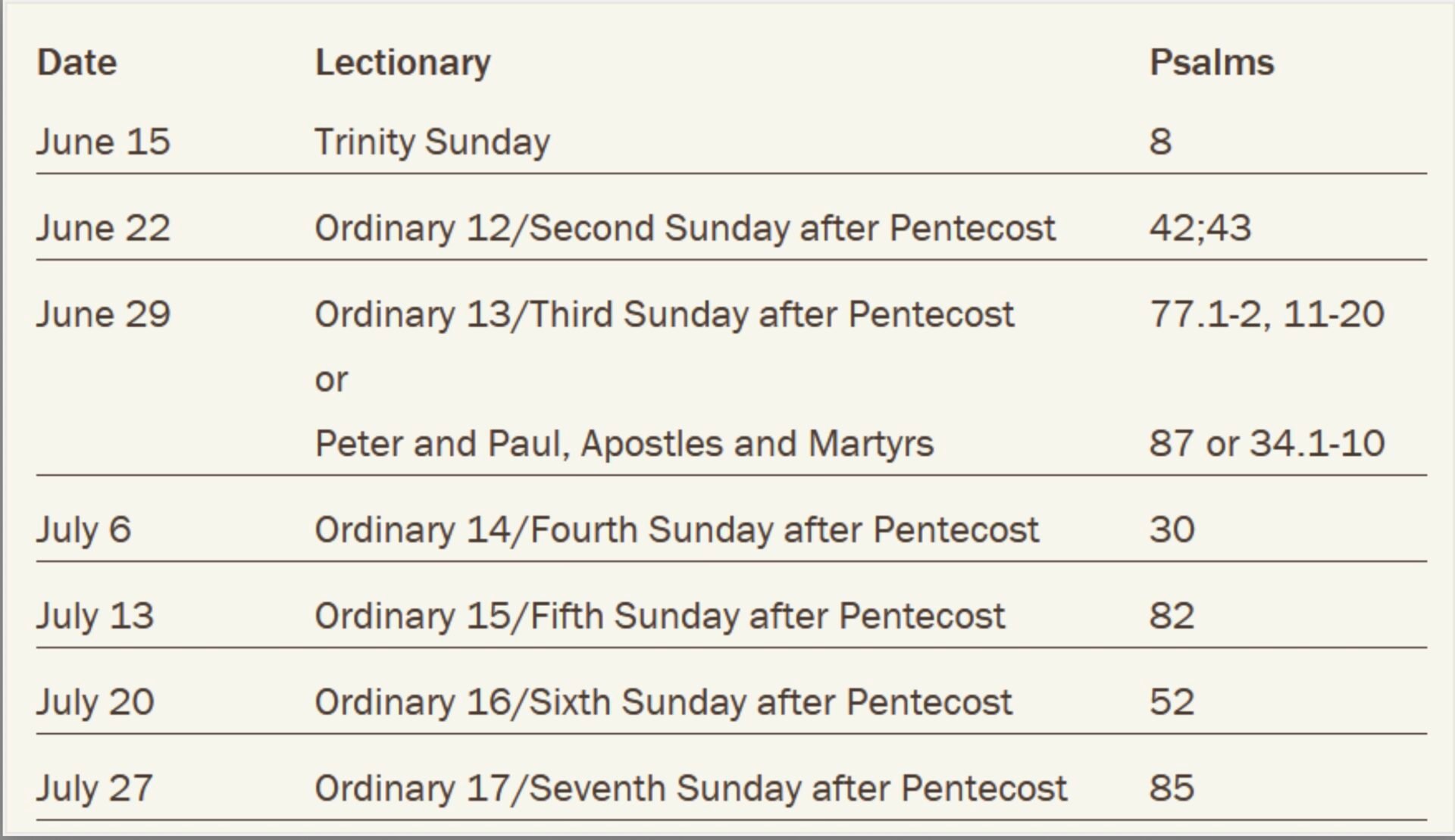

So we know which psalms will be used for any future date and this has allowed me to prepare the psalms set for these seven weeks. There are ten psalms in total, because 22 June has two psalms (42/43), and on the third week, there are three options from which to choose:

A number of churches still follow the practice of singing a response to the psalm and some, especially cathedrals, have choirs which sing the psalm of the day, in a form we call “chanting”. The practice of chanting the psalms stretches back into the mists of time, to ancient Jewish practices of chanting the Scriptures. This reminds us of how Jews and Christians across the ages have found in the psalms all the colours and hues and shades of the life of faith.

Prominent in this panoply of experience is the emotional highs and lows of life, with many psalms displaying a surprising honesty and frankness. Take for instance the famous words of Psalm 42.1-3 (using hereafter excerpts from my translation[2]):

1 As the deer longs for streams of water:

so longs my soul for you, O God.

2 My soul thirsts for God, for the living God:

when shall I appear before your face?

3 My tears feed me by day and by night:

ever saying to me, ‘Where is your God?’

Psalms range over much more than just personal angst; they encompass thoughts and fears, doubts and questions, hopes and aspirations, as in Psalm 42.9-11:

9 Let me say to God, my rock, ‘Why have you forgotten me?:

why must I walk in darkness, oppressed by an enemy?’

10 With death in my bones, my foes taunted me:

ever saying to me, ‘Where is your God?’

11 Why are you downcast, O my soul?

why are you troubled within me?:

hope in God, for I shall yet praise him,

my saving presence and my God.

In the darkest moments, even God is scrutinised and questioned, as in Psalm 43.2-3:

2 You are the God of my refuge,

so why have you abandoned me?:

why must I wander about in darkness,

oppressed by an enemy?

3 Send out your light and your truth,

let them lead me:

let them guide me to your holy hill, your dwelling place.

Yet it would be a mistake to think the psalms deal only with personal or private matters of faith, for many have in their horizon the whole creation and the ways in which it speaks of God.

At times, this language is highly dramatic, as in Psalm 77.16-18:

16 The waters saw you, O God,

the waters saw you and seethed:

indeed, the very depths trembled.

17 The clouds poured out rain and the sky thundered:

your lightning flashed back and forth.

18 Your thunderclaps roared in the whirlwind,

your lightning bolts lit up the world:

the earth quaked and shook.

And at times the place of humanity within the cosmos is brought into sharp focus, as in Psalm 8.3-5:

3 When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers:

the moon and stars, which you have set in place,

4 What is humanity, that you remember them?:

who are mortals, that you consider them?

5 You have made them little less than God:

and crowned them with glory and honour.

Of particular interest, given our own Federal election and the upheavals seen in the USA this year, is also the political dimension of many psalms, in which we find prayers for, or against, or about, earthly rulers. Psalm 52 is particularly striking in this regard and is worth a more fulsome exposition.

It commences with strident criticism of a corrupt political leader:

1 Why do you boast of evil, O mighty one?:

for God’s steadfast love never ceases.

2 Your tongue plots malice:

like a sharpened razor, O devious one!

3 You love evil more than good:

lying more than speaking the truth. Selah

4 You love the words that devour:

O tongue of deception!

The phrase “words that devour” is a potent and evocative image, yet the psalmist manages to find hope in God’s disempowering of this “mighty one”:

5 God will defeat you forever,

dragging you from your dwelling:

uprooting you from the land of the living.

And in response, those who have been suffering will take heart:

6 The righteous will see this and fear:

they will laugh at you and say,

7 ‘This one did not take refuge in God:

but trusted in great wealth to their ruin!’

And from this denouement emerges a poignant metaphor of wellbeing:

8 Yet I am like an olive tree

flourishing in the house of God:

trusting in God’s steadfast love forever and ever.

9 Always will I give you thanks, for you have acted:

with all your faithful people,

I will hope in your name, for it is good.

Another strongly political psalm from the trial is Psalm 82 (week 5 of the trial), which Zenger calls “one of the most spectacular texts of the Old Testament”.

Here the psalmist turns their attention to “the divine assembly”, and then presents us the voice of God addressing ‘other gods’, accusing them of being unjust and calling them out:

1 God stands in the divine assembly:

passing judgment in the midst of the gods.

2 ‘How long will you judge unjustly:

and set the guilty free?

3 ‘Give justice to the poor and orphaned:

vindicate the afflicted and broken.

4 ‘Rescue those living in poverty:

deliver them from the hand of the wicked.

Not satisfied with this opening critique, the psalmist then declares that God dethrones these ‘other gods’ entirely, mocking their inadequacy:

5 ‘They do not know, nor understand,

they wander about in darkness:

as all the foundations of the earth are shaken.

6 ‘I hereby declare, “Though you are gods:

children of the Most High, all of you,

7 ‘“Yet you will die like mere mortals:

like one of the leaders you will fall.”’

This psalm is deeply political because in the ancient world, the leaders of nations were often thought of as divine. So the ‘other gods’ could well be imagined as human rulers who behave as if they are godlike.

In the current climate, many people of faith will find such prayers to be a vital ballast against despair and paralysis in the face of earthy leaders acting as if they have divine sanction.

So may we join with the psalmist who concludes Psalm 82 with these words:

8 Arise, O God, and judge the earth:

for all the nations belong to you.

And all the people said, ‘Amen’.

An earlier version of this article first appeared in The Tidings, the quarterly newsletter of St Theodore’s Toorak Gardens, SA, where Matthew is parish priest.