There are many projects across the Anglican Diocese of Adelaide designed to help the homeless with basic needs but some Anglican leaders believe there are deeper moral questions surrounding the causes of the divide between haves and have-nots

Demand for free food services at St Jude’s Brighton has been rising all year but has skyrocketed throughout winter, providing a local snapshot of the wider fallout from the national housing and cost-of-living crisis.

Up to 120 people a week turn up for a free meal the parish launched a year ago and St Jude’s has burnt through many tens of thousands of dollars in food already this year.

It has run out of the good quality winter jumpers and coats it had in reserve.

“At Brighton we serve and minister with regulars who are living in their cars, sleeping rough in the streets, living week to week at camping sites, pitching tents anywhere, and some simply living in stiflingly unaffordable rentals,” says parish priest the Ven Sophie Relf-Christopher.

“Thank God, every few weeks somebody steps up to help with donations.”

It is time to address more fundamental systemic causes for the rise of homelessness and poverty

Apart from the weekly free meal, St Jude’s provides a free Community Pantry which works on a “give what you can, take what you need” basis, a free weekly Breakfast Club at Brighton Primary School (BPS) with the parish’s Pastoral Care worker and local churches serving 150-250 a week, a free catered playgroup, free food and hygiene support to BPS families in crisis, and a significant AnglicareSA Christmas collection.

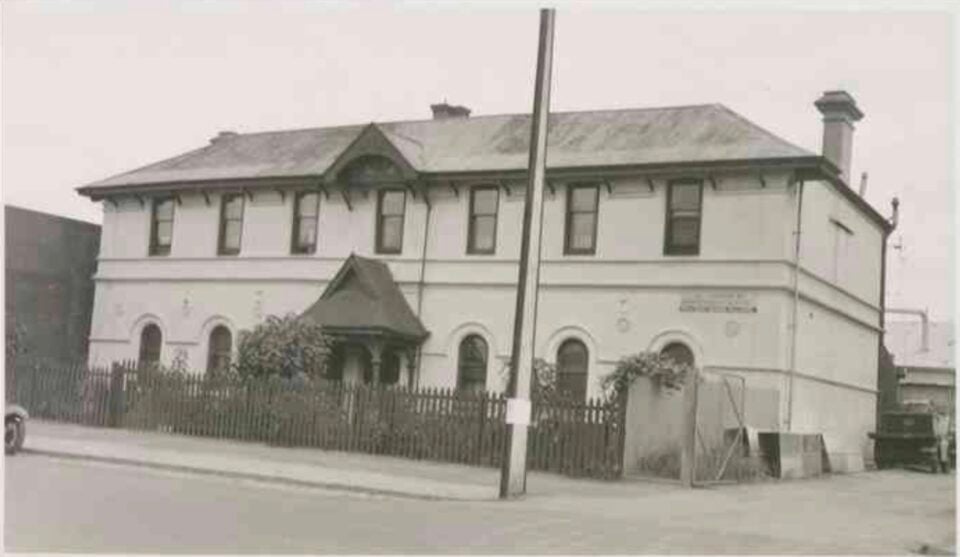

It is one of many such outreaches to the homeless and needy across the Diocese, including St Bede’s Semaphore’s Tuesday breakfast program that supports the homeless and those in local shelters, St Mary Magdalene’ has’s food program in the city, St Saviour’s in Glen Osmond, and St Mary’s South Road’s cheap lunches it offers at the Picket Fence Community Centre.

The list is not exhaustive and, of course, there are many other parishes support the homeless in other ways, such as the many parishes which support the Magdalene Centre with donations of money, food, and non-perishables.

But while meeting everyday human need is essential, it is time to address more fundamental systemic causes for the rise of homelessness and poverty, Relf-Christopher says.

“Churches have a vital part to play as we try and live out Jesus’ teaching. We must lead a revolution against the completely unsustainable and morally bankrupt social order that profits the few.

“We can do this by advocating for, as well as materially meeting the needs of people who are trapped in poverty and do not receive an equitable share of the riches of our society.”

Higher interest rates are putting the poorest at risk of losing the roof over their heads.

Anglicare recently noted the inequitable share of wealth and the apparent indifference to suffering among the less well-off.

“As Australia’s rental crisis deepens, public attention has shifted in a way we have not seen before,” this year’s National Rental Affordability Snapshot from Anglicare Australia says. “There are now daily news stories of people being unable to afford a place to live, families being evicted so landlords can dramatically increase rent, and talkback callers reporting that they fill dozens of applications only to be rejected repeatedly.”

Anglicare surveyed 45,895 listings across the country on a sample weekend in March. The picture it paints is a grim one. The agency measures rental affordability by the internationally accepted benchmark of less than 30 per cent of a household budget.

On this metric, only 16% of listings were affordable for a family of four on minimum wage and there were none at all for retirees on the aged pension, or individuals on JobSeeker or Disability Support Pension.

“The Snapshot shows that just four rooms in share houses are affordable to rent for a single person on JobSeeker and none for a young person on Youth Allowance. That means many people have no choice but to pay more than they can afford to keep a roof over their heads. They are forced to make choices about skipping meals, forgoing medications, or turning off the heater in order to make ends meet,” Anglicare writes.

Even for mortgage holders, higher interest rates are putting the poorest at risk of losing the roof over their heads.

“The rising number of homeless Australians shows just how unjust and unsustainable such sacrifices are.”

And leaving whole sections of society behind costs lives, as the harrowing government statistics from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare show.

“All this while fiscal policy has allowed house prices to balloon, which has not been seriously tackled by anyone,” Relf-Christopher says.

Most people in leadership have no real connection with society’s least advantaged

The Rev’d Ben Falcon, Acting Manager, Mission & Anglican Community Engagement with AnglicareSA, says the problem is not only fiscal and political, but theological.

“Jesus himself had strong words of condemnation for those who ‘devoured widows’ houses’ whilst putting on a show of piety (Mark 12:40; Luke 20:47),” he says.

“So, if God’s ultimate desire is to live at home with humanity in a renewed world, and Jesus bluntly condemns housing being taken away from those who need it, what must God think of a situation where so many people currently go without basic housing in Adelaide and Australia?”

Relf-Christopher agrees, adding that “privileged people do not own investment homes because they work 50 times as hard as their cleaner, they own them because the system, and the society it serves is indifferent to the cries of the poor and celebrates wealth through the disastrously faulty lens of meritocracy.”

The Rev’d Tim Sherwell from St Cuthbert’s in Prospect bemoans the absence of connection between those who have resources and those who don’t – sometimes within the ranks of the clergy.

“We really don’t have to look far to see this,” he says.

“For example, people of means are usually the only ones who can afford to train as clergy. That isn’t absolute but it is common. Who else can drop everything mid-life and take a punt on being ordained in four years’ time?”

The result is that most people in leadership have no real connection with society’s least advantaged, he says.

“They may not be considered wealthy, but there is little understanding of what it is like to lose half your income on rent and eat biscuits handed out by charities. It is little wonder the church doesn’t resonate with poverty when its own leadership cannot understand what poverty means in an experiential way.”

Relf-Christopher believes the Church has forgotten how to talk about making financial decisions as if God takes a keen interest in what we were doing with the gifts we are blessed to steward.

“Anglicans can do better. We can say more, we can bear witness more readily, we can steward our own resources with more intention, we can stir up the consciousness of a society that has lost its way. We can speak to our neighbours about what is going on.”