As we learn to live with Covid, Diocesan archivist Dr Sara Black looks back to how Adelaide Anglicans responded to an earlier pandemic

Lord Deliver Us

With South Australia’s borders open again and as we handle issues of vaccination, isolation, testing and tracking, it’s useful to remember that this is far from the first time we have managed pandemic illness in South Australia.

Quite apart from polio and other diseases we have battled over the years, there was also the big one, the Spanish Influenza that hit us at the end of World War 1.

The Spanish flu hit the SA newspapers in June 1918, before the war was even over. Reports were that it was “ravaging England” with hundreds of cases daily. By August it had “reached” America (in fact, we now know that it started there) and was causing many deaths. At around the same time a severe flu was going in Victoria, notably in the Broadmeadows Military Camp, but the authorities were firm that this was just a bad influenza of the normal kind.

Overseas, the virus would not be stopped. In September, South Australians heard that it was hitting South Africa very hard, and by early October the Port Adelaide News was able to say that “the outbreak of Spanish influenza seems absolutely world-wide.” Coffins were reported to be in short supply in Capetown.

The flu affected South Australians overseas before it got here. South Australian servicemen died of it in Britain after the war. Families mourned their lost children. We were affected along with the rest of the world; but to begin with this was from afar – a situation that would not last.

By the second week of October the authorities were considering how to prevent spread in South Australia. The Director of Quarantine (we had one in those days) “was using every endeavour to prevent the introduction into Australia of Spanish influenza”. It was decided to apply the provision of the Quarantine Act to influenza, so that a ship with an outbreak could be denied access to the port.

By mid-October authorities announced that South Africans arriving with influenza would be quarantined, and that the Commonwealth government was “taking steps to produce a vaccine”. The Chairman of the Victorian Board of Health, Dr E Robertson, stated that this virus could not be contained by isolation, as patients were infectious before they became ill, but that “the use of a vaccine might check it”. So then as now, we were stuck between the need to isolate and the need for vaccination.

The first South Australian known to have succumbed to the Spanish flu on this side of the globe was Mr Harold Youlton, of Parkside. He worked on an affected passenger ship and died in quarantine in Auckland in October 1918. That same month, Mrs Gertrude Wyatt, a popular Adelaide singer and entertainer, died in Johannesburg.

For a few months, strategies of excluding the virus from SA worked. In January 1919 the Gawler Bunyip reported “so far Australia has been the only country to escape the dreadful ravages of the Spanish influenza. The cases lying at Torrens Island [quarantine station] are a dread reminder to this city of the peril and pestilence at the gates.

That it triumphs over many modern preventives … and that its power does not abate with its extensive spread is show by the proportion of fatal cases. The casualty lists of war have stopped, but in America, Africa, India and Europe the casualties of peace reveal to us the terrible appropriateness of the prayer, ‘From war, pestilence and famine, good Lord deliver us!”.

There was much discussion of the power and meaning of prayer.

Bishop Thomas of our diocese authorised in February 1919 a prayer which read: “Almighty God, our help and defence, we heartily thank Thee for keeping this disease from spreading in our State; and we beseech Thee, continue to bless the means taken throughout our land for our protection, granting to those in authority wisdom and foresight, to all detained in isolation a ready spirit of obedience, and to the sick a full recovery of health. And this we ask in the name and mediation of Jesus Christ, Thy Son, our Lord. Amen.”

The Revd E H Bleby, at St Paul’s church in the city, chastised his flock that same month for staying away from church too much. He allowed that perhaps this was due to the heat, or the holidays, but also noted “the prevalence of Spanish Influenza in New South Wales and Victoria, and the probability that it will spread to South Australia, even if it has not already done so”.

He printed a different prayer, suggested for daily use: “O Almighty God, who in Thy wrath didst send a plague upon Thine own people in the wilderness; and also, in the time of King David, didst slay with the plague of pestilence three score and ten thousand, and yet remembering Thy mercy didst save the rest. Have pity upon us miserable sinners who now are visited with great sickness, that like as Thou then didst command the destroying Angel to cease from punishing, so it may now please Thee to withdraw from us this plague and grievous sickness; through Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.”

A contributor to the Guardian noted with disapproval that some people seemed to believe that those who faithfully asked God for protection would be spared. “It seems to me that plague, bush fires, drought, and other calamities are no respecter of persons” commented the writer. An article reprinted in the Guardian from the Gippsland Church Newsoffered some thoughts on this question, concluding “our church is justified not only in using the special prayer in time of plague but also in making general use at all times of the Collect for the second Sunday in Lent … in which we pray that God would “keep us both outwardly in our bodies and inwardly in our souls that we may be defended from all adversities, and from all evil through which may assault and hurt the soul.”

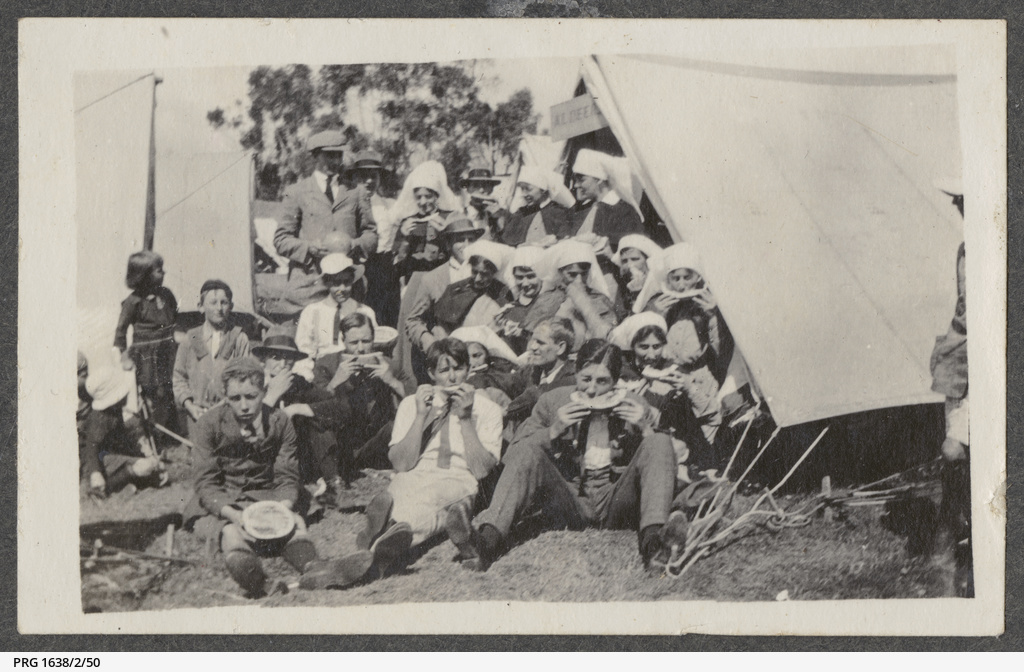

In February of 1919 many South Australians were stranded in Victoria behind a closed border. Among them was Rupert Hewgill, then rector of Walkerville. Revd Hewgill pleaded their case in the papers, advocating that they should be brought home to quarantine in some suitable place until “the danger was past”. This is, in the end, what happened. They were retrieved from Melbourne aboard special quarantine trains and spent a week quarantined in tent accommodation on the Jubilee Oval in town.

Revd Hewgill reported, “I am glad that I was one of the 640 interned on the oval for various reasons. Partly because anything would have been better than hanging about Melbourne wasting time and money and never knowing when it was going to end. Another reason is that we had a week of living in the open air. … It was delightful to wake up in the morning with those lovely hills for a bedroom wall and to have the great stars as companions for six perfect nights. … But best of all was the delightful surprise of finding out how nice we all were, how cheerful and pleasant and how determined to treat it all as a huge joke. There were nearly 700 of us, ranging from a judge of the Supreme Court down to – shall I say, parsons? … and through all those seven days I never heard an angry or even a disagreeable word. Our Holy Communion service, at the top of the grand stand … was a very real thing. Certainly Christ crucified was openly proclaimed for we were ‘seen of all men’.”

He concluded, “probably none of my readers have ever been in gaol. But if they have they will know that it is not the conditions that hurt. It is the fact that you can’t get out. How we used to envy the free people we could see passing on the road. And how our hearts ached for the prisoners [of war] in Germany. … Thank God they are all free now. But I hope I shall always have a tender spot in my heart for all prisoners and captives.”

Back at St Paul’s in March, Revd Bleby was exhorting his congregation to show their faith through continued church attendance, believing that the worst was over. However, he was too optimistic on this front. In fact, influenza had a further course to run in SA. It was not until 1920 that it died out. SA saw hundreds of deaths, including a bad outbreak in Port Pirie.

In April Revd Bleby wrote “we still need to pray … that we may be preserved from the epidemic which is now prevalent in many parts of Australia”. In May and June he continued to worry about the fears of his congregation which kept them away, and the role of the weather and the epidemic in depressing congregation numbers. He kept on printing the plague prayer each month. In September he reported with sadness the death from influenza of James Stanley Harden. Mr Harden was an unlucky young man whose leg had been shattered by an enemy shell on the beach at Gallipolis in 1915. Then four short years later, his life was taken by the influenza, aged 24 and his parents’ only son.

But all things come to an end. Just like that, from October 1919 it was over in the pages of St Paul’s parish newsletter. No more complaints from the rector about weather, epidemics and empty seats; no more plague prayer. The focus turned to the anniversary of war’s ending, the continued return of servicemen, and the holding of strawberry fetes for social and fundraising purposes.

In May of 1920, with the annual vestry meeting in mind, Revd Bleby crunched some numbers and reported “I officiated at 76 funerals, being 19 more than during the previous twelve months, this increase being the lamentable result of the epidemic of influenza”.

Comparing South Australia’s experience then to our experience now, there are a lot of parallels. Initial inertia on the part of authorities was followed by careful and largely successful preparations to keep the virus at bay. Nationally our geographic isolation and our control over land and sea borders were a huge help in this.

For South Australia, our remoteness as a state, our limited population density and the willingness of our population to follow the instructions of authorities and to act for the common good, all contributed to help delay and limit the effects of the pandemic. Vaccination, isolation and quarantine were crucial in the success of the public health response.

We also see the emotional struggle playing out, then as now, between our attachment to safety and our attachment to freedom. We hate to lose either one, even temporarily. Pandemics, it seems, have a way of exposing that.

In their prayers the people of Adelaide thanked God for his mercy and prayed for safety. In their daily lives they stayed home, feeling the pain of isolation, and did their best to follow the advice of the authorities. In between, they sought camaraderie where they could, tried their best to treat each other well, and muddled through. Through it all, their fears for their safety, fears for their freedom, and thankfulness for the gifts of life and health, were bound together through prayer.