By Peter Sandeman

When AnglicareSA’s Head of Homelessness Services Olive Bennell and I started working to end homelessness in the Adelaide Parklands five years ago, we focused on 16 long-term homeless Aboriginal people and their friends.

We wanted to help them access safe accommodation and health care to treat their chronic health conditions.

AnglicareSA purchased a property on South Terrace to provide a Healing Centre providing a culturally appropriate alcohol management program together with health care modeled on the successful AnglicareSA Brompton homeless person’s aged care facility.

All the other shelters are dry and are not culturally appropriate for Aboriginal people.

The Healing Centre was not supported by government. We couldn’t change the system.

We failed. Fifteen of those homeless people died and the fate of the remaining person is unknown.

Very little is known about the deaths of homeless people. The deaths of people living on the street and in the parklands aren’t counted. Unvalued and forgotten except by other street people and their workers, the deaths of homeless people are a hidden tragedy.

The cold weather reminds us just how tough living on the street can be.

The University of Western Australia with the Australian Alliance to End Homelessness (AAEH) identified 56 street homeless people who died last year in inner city Perth.

JobSeeker is too far low and a chaotic life on the street means you can’t search for the jobs that just aren’t there for people like you

Street people die young. Their average age of death was 47 years compared to average life expectancy of 83 years.

If the Perth CBD experience is extrapolated nationally then 424 street homeless people die in Australia each year including 20 street homeless people in South Australia.

In the US these deaths are termed “deaths of despair” due to drug overdoses, suicide, mental health, and alcohol related diseases amongst people who experience compound social and economic disadvantage. In short poverty. Street people are the result of a long process of social and economic exclusion.

We all know that JobSeeker is far too low and a chaotic life on the street means you can’t search for the jobs that just aren’t there for people like you.

Part of the problem is that navigating the silos between different parts of the homeless, health and human services systems is just too hard. It’s hard to detox from alcohol or drugs if the sobering up and rehabilitation services leave gaps putting you back on the street. It’s hard to access medical care if health services can’t find you because you don’t have stable accommodation.

Now the new Homeless Alliance model offers a better opportunity to meet the challenges of people living on the street as well as the wider homeless populations.

It’s a very difficult task, the pressures from residents and business in newly gentrified locations to remove homeless people from areas where they have traditionally been supported is growing. The recent issues around the communist party soup kitchen in Whitmore Square is just the most recent skirmish.

Simply moving street homeless people to another location will not work.

A clear plan is required to enable street homeless people to be supported to move on from a lifestyle that all to often becomes long term, and local residents need to be safe and businesses able to operate. This will require all parties to work together to have appropriate well-coordinated and effective services in the right locations.

The good news is that international experience through the Institute for Global Homelessness and the Adelaide Zero Project demonstrates there are service models that have been demonstrated to work. In Australia this work is now supported by the Australian Alliance to End Homelessness and the Adelaide Zero Project is now being copied interstate.

Jointly funded homeless services is the first step towards well-coordinated access to housing and care for homeless people. Hutt Street’s Aspire program demonstrates that long term tenancy support enables street homeless people to escape homelessness. The Housing First approach means the use of scarce hospital resources and emergency housing and recidivism are all reduced generating ongoing savings for government.

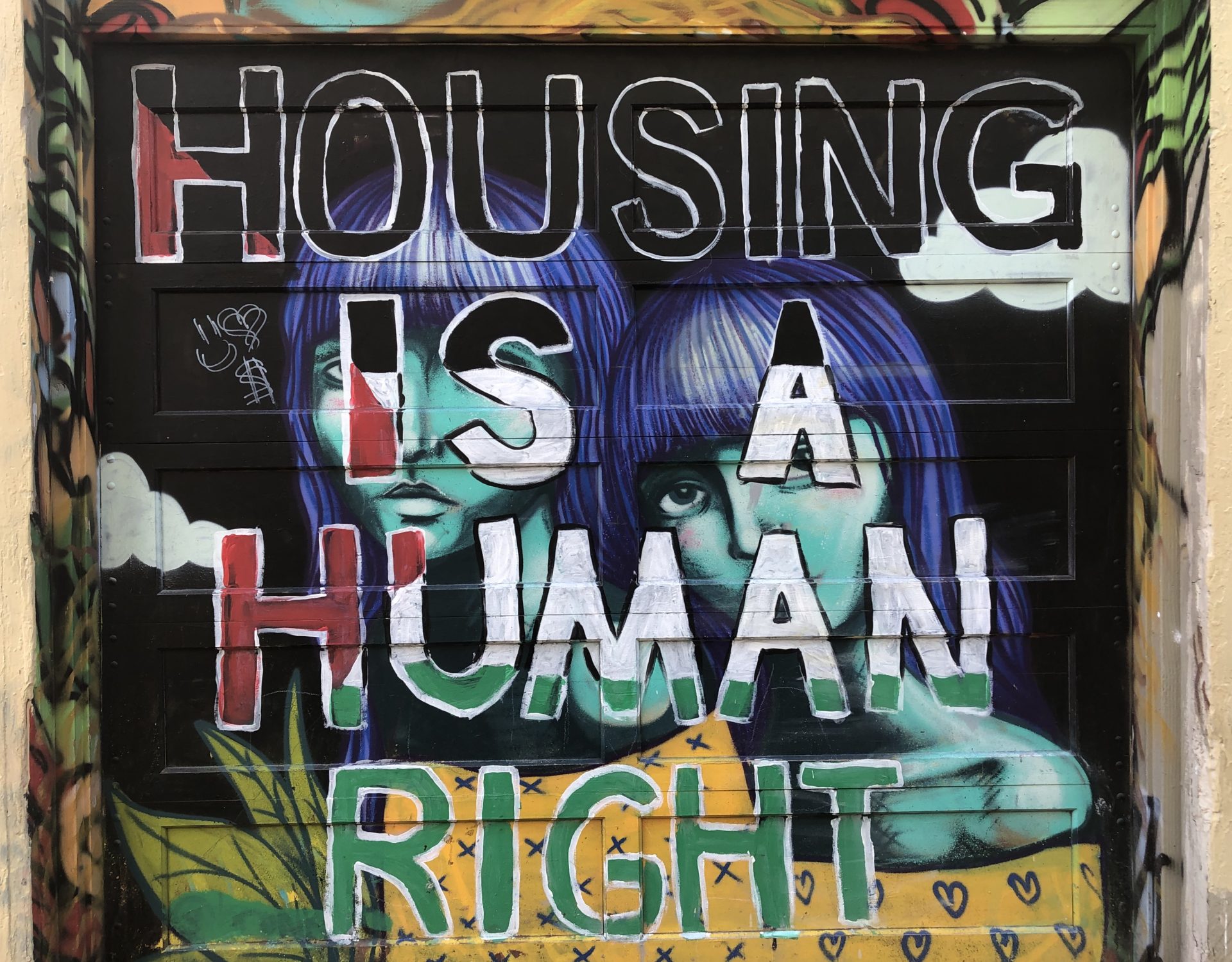

Its not just about saving money, we need to really value the lives of street homeless people.

Better coordination of housing and care will save and change the lives of homeless people. This is the yet to be fulfilled potential of the new Homelessness Alliances.

The Rev’d Peter Sandeman is the Canon for Social Justice and Advocacy and an Australian Alliance to End Homelessness Board Member